Universities - an engine for growth?

Are the "OxCam Arc" and university spin-outs the key for economic growth?

Hello, and welcome back to The Student Eye. We’ve had this week earmarked as one to write about the growth potential of universities for a while, so it was nice of Rachel Reeves to join us with her speech in Oxford on Wednesday. Today, we unpack the (mostly re-)announcements that came out of that, and break down all you need to know about the various “arcs”, “growth corridors” and “golden triangles” that have been discussed this week.

After that, we dive into the world of university ‘spin-out’ companies and just why they are so important for both higher education and the UK economy. We also look at whether the focus on the South-East and London is negative, realistic or, in fact, inevitable.

Finally, we ask the big question: is this what we want from our universities? Should higher education institutions really be optimised for economic growth or should the emphasis be firmly placed on teaching the next generation of business leaders?

As ever, please do send us on to anyone who you think may be interested and let us know your thoughts in the comments!

Universities and “going for growth”

Oliver Hall

Since last year’s general election in the UK it has been hard for anyone to avoid the government’s new mantra: it is “Going for growth”. This is very much a case of all the eggs going in one basket - without the UK escaping its current stagnation and dramatically exceeding treasury expectations of 1.3% growth in the coming year, almost all the Chancellor’s economic goals will collapse. On Wednesday, Rachel Reeves placed universities and the so-called “Oxford-Cambridge Arc” at the centre of those plans. Through connecting those two education and research hubs, greenlighting housebuilding, and more, Reeves believes that she can create “Europe’s Silicon Valley”.

The Oxford-Cambridge Arc?

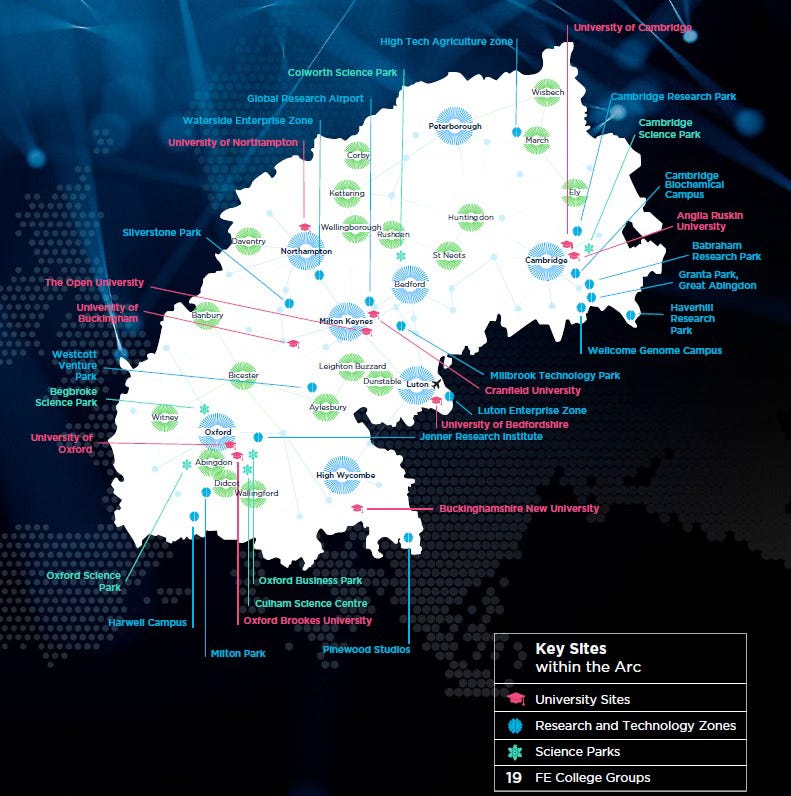

The “OxCam Arc” is the name for an area which stretches between Oxford and Cambridge universities, also encompassing Milton Keynes as a logistics hub. The scheme was originally drawn up in 2017 by the National Infrastructure Commission and set out to deliver a million extra homes and 700,000 jobs in the area. It was scrapped by Boris Johnson’s government in 2022 with an eye to more “levelling up”.

Science Secretary Peter Kyle confirmed earlier in the week that the government now intends to double the economic output of the region before Chancellor Rachel Reeves reiterated the message in her ‘growth speech’ in Oxford on Wednesday. Although no new money has been committed to the project, she vowed to “get going” on the railway between Oxford and Cambridge, via Milton Keynes, and appointed Lord Patrick Vallance as the new “Champion for the Oxford growth corridor”.

As well as the University of Oxford, the University of Cambridge, and their associated research centres, the area includes Silverstone, Luton Airport, and at least seven other universities.

If the government were to meet its goal, it would add £78bn to the UK economy by 2035, according to consultancy firm Public First. This development is clearly a vote of confidence in universities to not only educate the next generation of business leaders but also deliver economic growth themselves. It is also another case in point for the focus of this investment in the South of England - there is a distinct lack of focus on creating similar investment ‘clusters’ in the North and North East around successful universities such as Manchester and Liverpool.

The ‘Oxbridge’ universities command far higher endowments than most other UK institutions and have therefore been able to invest more heavily in research in recent years. This is why projects such as the Oxford Science Park exist and why the Larry Ellison Tech Institute has pledged to invest over £100m as part of a partnership with the University of Oxford. Places like this have been key in facilitating the growth of university spin-out companies that have attracted large investments to the area in the last decade.

What are “spin-outs”?

Spin-out companies, commonly known as spin-outs, are companies that are founded based on intellectual property (IP) created during research at a university. Usually, the university in question will also play a key role in providing an enterprise team to aid in this process as well as access to funding, workspaces, and more.

Typically, researchers at a university will make an "invention disclosure” which informs the university of something that they have discovered and believe to have commercial potential. Most universities have a team that supports commercialisation, called a technology transfer office (TTO), that will work with academics to analyse the potential of their ideas, move to protect IP, and advise on the next steps. After that, there will be a decision made about whether to license the IP out to another existing company or to create a spin-out based on it.

“Spin-outs from the University of Oxford alone are now estimated to be valued at £6.4 billion.”

Traditionally, Silicon Valley has been the home of many of the most successful of these including Google (Stanford), Bose (MIT), and Boston Dynamics (MIT), but the last decade has seen a dramatic increase in the commercialisation of research in UK universities. Indeed, spin-outs from the University of Oxford alone are now estimated to be valued at £6.4 billion.

Why do they matter and what is the opportunity?

Despite the challenges currently facing the UK’s higher education sector, it undoubtedly hosts several of the world’s leading research universities. In recent years, especially since leaving the European Union, there has been much talk from government about emulating Silicon Valley and optimising regulation to this end. Spin-outs could help solve current growth problems, unlock value in the private sector, create jobs, raise investment in the UK, and deliver benefits for society as a whole.

Equally, some level of self-awareness is needed when considering the size of the potential opportunity. The amount of seed funding available in the UK is far smaller than in California and actively competing with that market is unrealistic. Instead, universities here will have to focus on identifying and exploiting niches in which the UK can be a world leader, such as humanities and biomedicine.

What now?

In November 2023, Professor Irene Tracey and Doctor Andrew Williamson produced an independent report for government on this issue to explore the opportunities and how to maximise them.

Firstly, the report identified the so-called “golden triangle” that encompasses Oxford, Cambridge, and London, as the centre of most UK success. In 2021/22, spin-outs in this area raised £3.94 billion - some 74.5% of investment in the whole country. The survey attached to the report showed that the biggest problem in developing elsewhere was finding funding outside of the south-east.

The major obstacle holding back spin-outs in the UK at the time of the report was a lack of experience in commercialisation. Since then, TenU, a collaboration of university TTOs, has published best practice guidance for these spin-out deals. In the past decade, UK universities have held between 18% and 25% of equity in successful spin-outs, far more than competitive global institutions. US universities ‘reliably report’ taking 3-10% equity stakes and TenU has now proposed a 10-25% norm (pre-dilution).

Irene Tracey made the case for continued investment in this area in an article before October’s budget, pointing out that spinouts from UK universities have created 29,000 jobs since 2014. However, she also highlighted that for all the progress made, there is still a huge gap in the proof-of-concept (POC) funding which allows researchers to take their projects from research to market. This is another area in which the large endowments of US universities give them much more flexibility to invest heavily at an early stage.

In response to Casey and Williamson’s report in 2023, the government committed £20 million of POC funding over three years. That may sound substantial but it is comparable to what Stanford University invests on its own every single year.

“This (topic) one asks the question: what purpose do our universities actually serve?”

What are universities for?

Perhaps more than any topic that we’ve covered in The Student Eye so far, this one asks the question: what purpose do our universities actually serve? On the one hand, it is easy to be excited by their potential to drive economic development. On the other, many universities are on the brink of financial ruin - the reality is that most do not have the economic capability to develop this aspect of their offerings.

One of the report’s conclusions is that: “Supporting the creation of spin-outs must not result in a net cost for UK universities with already challenged operating budgets and declining real-terms tuition fees.” Other than for a small selection of the Southeast’s very most esteemed institutions with high research capability, that goal might be unrealistic. Given that almost all universities are making difficult decisions on cuts to courses and jobs, it is fair to assume that their focus should remain on educating not commercialising.

“Harvard University has a central endowment more than 42 times that of Oxford”

Top universities are, however, some of the UK’s most prized assets and for a government so committed to economic growth, it would be misguided not to make use of them. The challenge will come in bridging the financial gap to the vast endowments that American institutions enjoy. The complication of the college system within the University of Oxford (the richest in the country) means that it only has a central endowment of £1.9 billion. To put that large-sounding sum in context, Harvard University has an endowment more than 42 times that, coming in at $52.3 billion.

Some restructuring can be done to grow endowments in the UK and more government funding can be directed towards research and commercialisation. It seems unlikely, however, that the UK will ever be able to fully replicate Silicon Valley in Oxford, Cambridge, and Milton Keynes.

Around the country

Each week, we bring you a selection of our favourite stories from student publications around the UK and several of those pieces are below as usual.

Firstly though, we wanted to touch on the substantial, if unsurprising, job cuts at Cardiff University and Durham University. We have already covered the financial crisis in higher education in a broader sense but next week will be writing about these cases specifically and why more of the same may be on the way.

Student Protestors Clash with Security and Audience at Graduation Ceremony

Mihai Rosca wrote for Epigram about clashes between five pro-Palestine student protestors, audience members, and security.

OA4P occupies the Radcliffe Camera

Cherwell also covered dramatic pro-Palestine protests this week at the Radcliffe Camera library in the centre of Oxford. Protesters occupied the building and sat outside on window ledges - some left voluntarily and police abseiled down from the roof to remove the others.

The University of Leeds Flees X

The Gryphon covered the news that The University of Leeds is stepping away from X, stating its “divergence from the values of “collaboration, compassion, inclusivity and integrity”. It marks an interesting moment and asks whether other institutions may follow suit given some of the content now acceptable on the platform.